1115

THE POWER OF THE DOG

By David Hancock

It is probable that the first dogs domesticated by man were hunting dogs, not hounds in the manner of today's specifically bred animals but wolf-like creatures able to track or catch wild game. In time man developed huge hounds capable of pulling down the bigger quarry such as deer, wild bulls, boar, buffalo and other animals, nearly always bigger than the dogs. As man settled and developed he found time for sport and bred dogs able to support his new pastime. Valuable hunting dogs were traded and in due course breed types evolved to suit the style of hunting and terrain being used. When tribes migrated they took their hunting dogs with them. The history of dog is inseparable from the history of man. Against that background the development of dogs for a particular function can be traced. But it must be kept in mind that today's international boundaries do not always have relevance in breed origins and that the vigorous trade in useful dogs meant that hunters would always strive to obtain dogs more proficient than their own. The power of the dog became the power of man.

Big, muscular 'seizers' were valued by early man as big game hunters, capable of pulling down boar and elk, even aurochs. But there were also the 'chasers', the par force hounds, hunting using scent and sight, at pace, supported by the broad-mouthed 'seizing' dogs, the strong-headed, wide-jawed, modified brachycephalic type, used at the kill in medieval hunting and as capture-dogs since, the world over. These dogs have been used as hunting mastiffs or matins for over a thousand years. There are in addition however, what might be called 'running mastiffs', huge par force hounds that hunted using sight and scent, rather like leopards in the cat family. Their surviving examples are breeds like the Great Dane, the Dogo Argentino, the Rhodesian Ridgeback, the Broholmer of Denmark and the Catahoula Leopard Dog. These were hounds of the chase, too valuable to be sacrificed at the kill, not trained or bred to be recklessly brave and prized for their looks more than any holding dog breed. They all excelled at 'steeple-chase-hunting' - following their quarry using sight and scent at great speed, over many obstacles, and deserve our admiration. Such dogs relied on their power.

A wide range of powerful dogs bred to protect livestock have been utilized from the upland areas of Iberia in the west, right across to Iran and on to the highlands of Eastern Europe, from mountainous Balkan regions in the south and northwards to former Soviet states. Sometimes they are called shepherd dogs, others mountain dogs and a few dubbed 'mastiffs', despite the more precise use of that word in modern times. Their coat colours can vary from solid white to dark-grey and from a rich russet to solid black, often with tan. Many that developed as breeds are no longer used as herd-protectors and their numbers in north-west Europe seriously declined when the use of draught dogs became a victim of the mechanized age. A number of shared features connect these far-flung types: a dense weatherproof jacket, a substantial build, an impressive magnanimity and a strong instinct to guard livestock placed under their supervision. As a group, they would be most accurately described as the flock guardians; in Britain in the distant past they were referred to as 'shepherd's mastiffs', but they were valued all over Europe. In the Pyrenees, you have the Pyrenean Mountain Dog on the French side, the Pyrenean Mastiff, similar in build and coat, on the Spanish side. Their breed title is essentially different; their role and employment one of protection not seizing and holding. But cattle-control demanded greater immediate power from their canine controllers.

Here is a mental exercise for all owners of Corgis, Lancashire Heelers and Australian Cattle Dogs. Imagine going into a field of hefty lively bullocks, then getting down on your hands and knees and just picture the menace faced by your dogs when the cattle surround and threaten you. I write this from my memory of a story told to me on the Black Mountain on the Herefordshire/Welsh border, when I was researching the bob-tailed heelers found there. A cattle farmer told me of when he once had a diabetic attack when in a field containing twelve well-grown bullocks. He 'came to' surrounded by determined bullocks but protected by two of his heelers. Lying vulnerably on the ground, he saw the menace his dogs experienced every day, and, for the very first time, from their perspective. This experience gave him a new respect for his agile, steadfast and highly focussed dogs. Every year in Britain dog-walkers are harmed by defensive cows, usually with calves, when walking in pastureland.

Any 30lb dog facing a one-ton beast has my admiration; facing a dozen, with horns as well as hoofs, takes a very special kind of dog. Dogs serving man by herding horses, driving cattle or coralling wild bulls survive through their great agility, but they are chosen for their courage. Without courage, they wouldn't be exercising their agility; they are remarkable dogs, the smaller heelers especially so. They need mental power as well as sheer courage. I first became aware of the heeler's power in an unusual way: playing football with a fellow twelve year old who had a Pembroke Welsh Corgi. The dog 'played' football with us, and every time it was threatened by a swinging foot, it flattened instinctively and the foot cleared its head. This was done with remarkable timing. I was impressed; later on, when this dog was mated to a local terrier, I obtained a pup, such was my admiration. This 'drop-flat' technique is a vital survival technique when lashing hooves respond to a small dog's urgings. Clever experienced heelers will nip the rear foot which the cow is standing on, rather than the one free to kick. This power to control is nearly always from behind: a quick nip and away. It demands immense courage and determination from the heeling dog.

This ability was valuable when cattle needed to be moved: in markets or when loading lorries or railway trucks. Short-legged, terrier-like heelers were not an unusual sight in Britain in the last two centuries. If they had been gundogs or hounds whole libraries would be filled with tales of their deeds. But they were used by shepherds and stockmen not squires and little has been recorded of them. But when, as a student over sixty years ago, I had summer jobs on farms, it was not unusual to come across small nondescript foxy-headed dogs working cattle. I was reminded of them a few years later when, on an expedition to Norwegian Lappland, I came across Buhund-type dogs on the farms there and Lapphund-type dogs accompanying the Lapps on reindeer drives. Herding livestock requires sheer power from the herding dog, a combination of mental strength and physical capability..

The Australian Cattle Dog is respected in many countries for its mental toughness, physical robustness and serious approach to work. In his 'Hunting Big Game with Dogs in Africa', the American Er M Shelley, gave an admiring pen picture of one of these dogs. He described her as: "...a wonderful hunting dog. She could trail nearly as well as a hound, and, when it came to fighting in dense places, I have never seen a dog that could compare with her. She possessed the power and had the courage to force a lion from place to place in dense cover, while large packs of dogs could not move him at all. In after years she was used by Mr Rainey to bring both lions and leopards out of dense reed beds, where his entire pack of forty or fifty hounds and Airedales could not move them." That is some tribute from a man with immense experience in hunting big game. That is an exercise in canine power.

The Australian Cattle Dog is believed to come from root stock of two Scottish blue merle working collies crossed with dingo, with Dalmatian (much disputed) and Kelpie blood introduced later. I see Bull Terrier features in the anatomies of many ACDs but am told that the outcross to the Bull Terrier was not considered a success and not favoured. The dingo blood is alleged to have produced the inclination to creep up behind cattle and bite them. But there has never been a shortage of British working collies with the instinct to get behind stock and nip it into compliance. I once owned two farm collies/working sheepdogs that would nip the hocks of cattle as a herding tactic without any training to do so.

The origins of heeling cattle dogs are often the subject of fierce debate. EC Ash, in his Practical Dog Book of 1930, somewhat ignorantly wrote: "...they are a cross of Shetland Sheepdog with the Sealyham Terrier, and possibly Border Terrier..." But nine years later, was writing, just as vacantly: "I am of the opinion...that the Welsh Corgi (Pembroke) is an Alsatian cross." About that time, Theo Marples, no expert on the history of the dog, was writing: "Probably the Welsh Sheepdog and the Bull Terrier had a hand in his making." Clifford Hubbard however, who made a comprehensive study of the Welsh breeds, linked the Pembroke variety with Flemish weavers who settled in the Haverfordwest area in the eleventh century. He considered that these migrants brought their Schipperke-like dogs with them to provide an essential ingredient in the emerging breed.

But what about the only surviving English heeler breed, the Lancashire Heeler? With only around 130 being registered annually this breed now appears on the KC's vulnerable breeds list. This is worrying, firstly because we have lost too many of our native pastoral breeds, and, secondly because this is a breed well worth saving. A foot high, smooth-coated, black and tan or liver and tan, lively and perky by nature, they represent an ideal companion dog for many households. I do hope the show ring fanciers keep faith with the historic design of this breed and not produce, in time, Dachshund-like specimens with narrow pointy jaws, bent legs and too low to ground a build. This is essentially a natural unexaggerated working breed, deserving to be conserved as just that.

It is interesting that dogs used with cattle can vary from those substantial enough to impose their will, like the Bouviers and the Fila breeds, to the little heelers. All these dogs need considerable courage but the little breeds especially so. They combine skill with guts. In his fascinating book, Dogs and their Ways, published in 1863, the Rev. Charles Williams wrote: "Lord Truro told Lord Brougham an anecdote of a drover's dog, whose sagacious conduct he observed when he happened on one occasion to meet a drove. The man had brought seventeen out of twenty oxen from a field, leaving the remaining three there mixed with another herd. He then said to the dog, "Go, fetch them," and he went and singled out those very three." That takes skill and courage. The larger cattle dogs overseas are well worth studying. It is interesting that dogs used with cattle can vary from those substantial enough to impose their will, like the Rottweiler and the Beauceron in Europe, the Fila breeds - the Fila de Sao Miguel for example, the Presa breeds - the Perro de Presa Mallorquin/Ca de Bou or cow-dog of Mallorca, (Fila and Presa identifying the 'gripping' breeds), the Bardino Majero of the Canary Isles and the Perro Cimarron of Uruguay, to the little heelers. All these dogs need considerable courage but the little breeds especially so. They combine skill with guts.

Cattle dogs have never enjoyed noble patronage, featured in fine art or carved a niche for themselves away from the pastures. That may not strengthen their image but should not weaken their case for conservation. The Filas or holding dogs in particular face serious threats in the developed world as ignorant law-makers punish them for the misdeeds of their owners. Yet from the stock-pen to the boar hunt such dogs merely did man's bidding; they are well equipped to continue this in many different ways for a long time to come. Bred for their courage - they certainly displayed it!

As long as man needs beef and milk, he will need clever, brave dogs to support him. Butchers may no longer need strong-headed dogs to pin cattle at abattoirs or markets and the droves have long lost their role. But stockmen in many countries still need cattle dogs, dogs agile enough to dodge lashing hooves and sometimes heaving horns too, and brave enough to undertake the task in the first place. These are not just another breed or collection of breeds. They are very remarkable dogs. As the lifestyle of modern man heads towards total urbanization, sporting and pastoral breeds face an uncertain future. We dispense with their skills at our peril; it would foolish indeed to assume that the uncertainties of the future will not in any foreseeable circumstances present a need of such unique talents - and such courage.

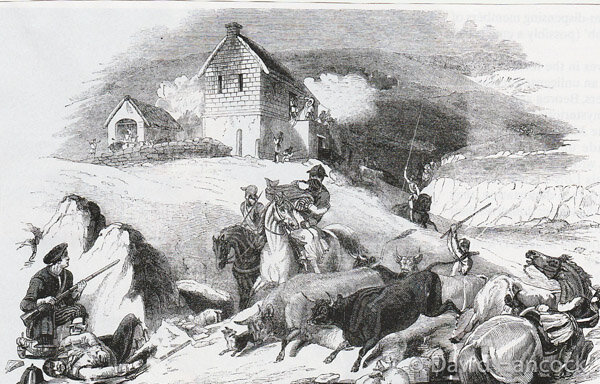

Charles Williams, in his Dogs and Their Ways of 1863, wrote: “Drovers’ dogs are singularly prompt in their actions, and all who have watched them in the crowded, noisy, tumultuous assemblage of man and beast, that used weekly to occur in Smithfield, must have observed their intelligence and courage. Nor in the busy streets of London, through which drove after drove of cattle were taken, could the same qualities fail to be noticed by any sagacious looker-on. These dogs were accustomed to bite severely, and always attacked the heels of the cattle, so that even a fierce bull was easily driven by one of them.” These words from Shirley Toulson’s The Drovers (Shire Publications, 1980) provide an immediate concept of the significance of historic markets and the total reliance on the power of dogs to get the livestock to market: "...for centuries, at least from the time of the Norman conquest to the establishment of the railways, the most important long-distance travellers were the drovers…they formed great cavalcades that blocked the way for other travellers for hours at a time…if farmers did not want their cattle to join the drove they had to make sure they were safely enclosed…Some parts of the drove-ways were also used to transport pigs, sheep, geese and turkeys, and these animals also had to travel great distances.” The drovers relied on the power of their dogs to get their livestock to market.

It’s difficult to visualize nowadays six thousand sheep being moved on foot in more or less one huge flock from east of the Pennines to the markets of Norfolk and Smithfield. It’s not easy to think of thousands of cattle, sheep and even geese being shepherded by a small number of dogs from remote rural pastures along established drove-roads to city markets – and the dogs either accompanying the mounted drover homewards or then being left to find their own way home. These were very remarkable dogs, dogs with power, giving man power.

In his Cynographia Britannica of 1800, Sydenham Edwards writes, of the drover’s dog: “…he appears peculiar to England, being rarely found even in Scotland. He is useful to the farmer or grazier, for watching or driving their cattle, and to the drover and butcher for driving cattle and sheep to slaughter; he is sagacious, fond of employment, and active; if a drove is huddled together so as to retard their progress, he dashes amongst and separates them till they form a line and travel more commodiously; if a sheep is refractory and runs wild, he soon overtakes and seizes him by the foreleg or ear, pulls him to the ground. The bull or ox he forces into obedience by keen bites on the heels or tail, and most dexterously avoids their kicks. He knows his master’s grounds, and is a rigid centinel on duty, never suffering them to break their bounds, or strangers to enter. He shakes the intruding hog by the ear, and obliges him to quit the territories. He bears blows and kicks with much philosophy…” Those picturesque words are a concise summary of the dogs’ purpose, as well as showing their prowess as heelers too. But heeling prowess can be matched by the value of the sustained 'treading' power of dogs used in mechanical devices not just in kitchens as turnspits but on the treadmills used to power agricultural equipment too. But pulling power is better documented as the canine hauliers demonstrate.

It's unjust in many ways for haulage dogs to be remembered solely through demonstration-carts at shows or in snow-sports or cross-country events in northern countries. The service to man of dogs that could haul laden carts and sledges in town streets or arctic conditions was considerable. We perpetuate baiting dogs but not carting dogs. In Europe the strapping cart-hauling dogs were mainly crossbred and so unlikely to be restored as a lost breed might be. They weren't prized for the pureness of their blood but for their pulling power. In Eastern Russia and North America, on both sides of the Bering Straits, primitive people benefitted when determined strongly-made dogs transported their goods over unforgiving terrain. Unlike the lost cart-dogs we still have the Samoyeds and the husky breeds to perpetuate the sled-dogs. Long forgotten are the dogs employed to haul agricultural machinery used to work the land or those used by primitive people in North America to pull loads strapped to long poles and dragged along the ground. This wasn't merely a test of physical power but a test of will - sheer determination, rather as pulling contests for Staffies are sometimes held.

To this day on the continent of Europe, dogs are still used to pull carts, as the Bernese Mountain Dog fanciers sometimes demonstrate at their shows in Britain. Just over a century ago, Professor Reul, one of the founders of the Belgian Club for Draught Dogs, wrote: "The dog in harness renders such precious services to the people, to small traders and to the small industrials (agriculturists included) in Belgium that never will any public authority dare to suppress its current use." Taplin, writing in The Sportsman's Cabinet of 1804 on Dutch dogs, stated that: "...there is not an idle dog of any size to be seen in the whole of the seven provinces. You see them in harness at all parts of The Hague, as well as in other towns, tugging at barrows and little carts, with their tongues nearly sweeping the ground, and their poor palpitating hearts almost beating through their sides; frequently three, four five, and sometimes six abreast, drawing men and merchandize with the speed of little horses." In Britain too, draught dogs were widely used, until, because of the huge increase of traffic in London, compounded by the widespread ill-treatment of the dogs, led to this practice being forbidden by law. But the power of the 'haulage dogs' over snow has outlasted the use of such worth in more southern climes.

The fame and value of the northern haulage dogs has long been acknowledged, with many remote areas having their own version to meet their particular needs. In this way, you can read of the Mackenzie River Dog, the Klamath-Indian Dog, the Baffinland Husky, the Toganee, the West Greenland Husky and the Kingmik. The Indian Wolfdog or Timber-wolf Dog came from an outcross to the wolf to increase pulling-power but their aggression lessened their use, except as lead-dogs. In Russia, the North-easterly Hauling Laika was the favoured sled-dog of the most extreme eastern part of Siberia. In North America, in due course, as sled-racing became popular, breeds like the Chinook, the Aurora Husky, the Huslia Husky and the Kugsha Husky emerged, with the latter specialising in heavy weight pulling. The nomadic Indian tribes of North America also used 'travois dogs' to pull loads on pole-ends dragging along the ground instead of on ski-like runners. This once gave us the now long-lost Hare-Indian Dogs, the Plains-Indian Dog and the Sioux Dog. There is something very special about this group of dogs, they display a definite 'presence'. I have seen a Chinook that was so majestic that it simply took your breath away. As a type of dog, this whole spectrum of types and breeds, deserve our admiration for their past feats in support of man.

The use of dogs in the frozen north has long fascinated those of us living in warmer, more hospitable climes. The canine support for arctic expeditions has been extraordinary, with many being entirely dependent on dog-teams as an essential unmatchable transport-system. Ponies too played a role but the sled dogs underpinned most polar expeditions. Their quite remarkable endurance of those conditions, allied to their astounding feats of haulage, exemplify yet again dog's unique contribution to man's activities in every century. The canine polar role demanded not just the power and stamina to haul a sledge day after day across frozen unforgiving terrain, but the ability to withstand extreme temperatures and perform exacting duties without losing too much energy in doing so. Of course those dwelling in arctic places, such as North America and Siberia, bred dogs that could meet these demanding criteria, seeking dogs that were not too huge as to need undue feeding requirements but having the construction and the coat to allow them to succeed. Such dogs had to have superb feet, weatherproof coats, massive amounts of stamina and great strength of mind and body. Exhausted dogs die, poor hauliers don't survive and dogs lacking the fundamental qualities have no value to the people living in or travelling through such a challenging climate. Some estimates have suggested that there were around 20,000 Canadian Eskimo Dogs alone in the 1920s, but only 200 some fifty years later. The power of the dog in severe conditions has not just faded in extreme northern regions. Such canine value has been matched by heroic deeds in the oceans and in the mountains of Europe.

Heroes were much a feature one hundred years ago, whether intrepid explorers, valiant soldiers or pioneer airmen. Canine heroes too were once much vaunted in those more romantic times, when dogs were valued not for what they looked like but for what they could do. Throughout the 19th century, both the Newfoundland and the St Bernard were very much the hero-breeds. Landseer's celebrated painting "A Distinguished Member of the Humane Society" drew attention to the feats of the Newfoundland. His "Alpine mastiffs re-animating a distressed traveller" of 1820 paid homage to the St Bernard. The heroism of one St Bernard, "Barry", was legendary. In his "Dog Heroes" of 1935, Peter Shaw Baker writes: "Barry, however, served the hospice faithfully for twelve years. Whenever the mountains were enveloped in fog or snow, he set out in search of lost travellers. He used to run barking until he lost breath, and would frequently venture on the most perilous places. When he found his strength insufficient to draw from the snow a traveller benumbed with cold, he would run barking back to the Hospice in search of the monks..." The Newfoundland too drew the writers' attention.

Edward Jesse, in his "Anecdotes of Dogs" of 1846, writes: "A gentleman bathing in the sea at Portsmouth, was in the greatest danger of being drowned. Assistance was loudly called for, but no boat was ready, and though many persons were looking on, no one could be found to go to his help. In this predicament, a Newfoundland dog rushed into the sea and conveyed the gentleman to land..." Margaret Booth Chern, in her "The New Complete Newfoundland" of 1975, describes how: "Every Christmas season brings to memory the heroic rescue of the 90 passengers and crew of the SS Ethic by a stalwart Newfoundland. For the number of people saved, it is believed to be the record for any dog of any breed...The Newfoundland swam out through a sea in which no man could possibly have survived. The powerful dog made it to the ship and carried a lifeline back to the shore..." Name another animal that could have performed such a feat!

The word power has a number of meanings: ability to do or act; vigour, energy; authority over; capacity for and exerting mechanical force - as in horse-power. All the meanings that apply to dogs are admirable. They have the ability to act in a wide variety of ways; they possess immense vigour and energy; they exert authority over sheep, cattle and their prey in the hunting field; on a turnspit, hauling a sledge or cart they demonstrate an ability to exert mechanical force. We await a drone to conduct sea and snow rescue - until then dog-power reigns supreme!