1104

GUARDING THE TERRIER HERITAGE

By David Hancock

“The terrier, among the higher order of sportsmen, is preserved in its greatest purity, and with the most assiduous attention; and it seems of the utmost importance not to increase its size, which would render him unsuitable for the purpose in which he is employed, that of entering the earth to drive out other animals from their burrows, for which his make, strength, and invincible ardour, peculiarly fit him. On this account, he is the universal attendant upon a pack of fox hounds, and though last in the pursuit he is not the least in value.”

Thomas Brown, from his Biographical Sketches and Authentic Anecdotes of Dogs, of 1829.

The emergence of the terriers and their subsequent evolution into breeds has left us with a dilemma. Do you breed them to fit the accepted show-ring phenotype or to respect their working function? If you stop for a moment thinking about the type of dog that goes underground and consider other small mammals that do, you obtain a different mental image. Rabbits, badgers, foxes, prairie dogs and especially moles, operate very successfully underground. Does coat colour matter for them? Do they need to be well-boned, have very long muzzles, excessively long coats, a ‘cobby’ build, or resemble in any way the type of horse called a hunter? What do those which operate above and below ground have in common? Three particular features come to mind: appreciable elasticity of torso, an eel-like construction for the neck and back (which is comparatively long) and a short thick coat. But what physical features do the Kennel Club approved standards for registered terrier breeds demand? It is worth a glance at them.

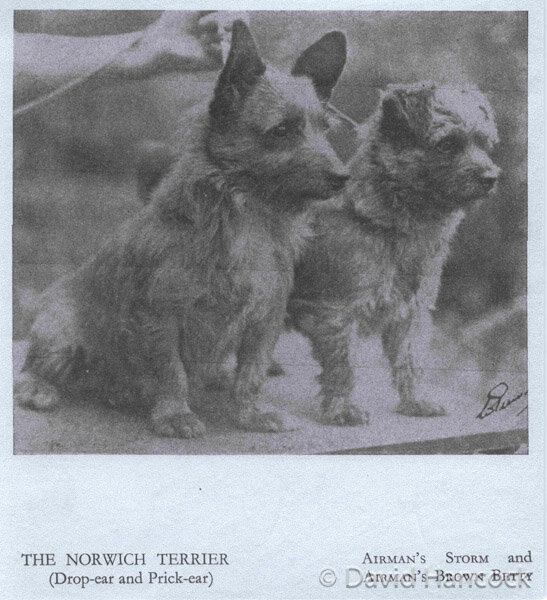

Airedales, both varieties of Fox Terrier, Norfolk and Norwich Terriers and the Welsh Terrier are required to have short backs. The West Highland White, Norfolk and Norwich Terriers are expected to have compact bodies. The Welsh Terrier has to have straight front legs, as does the Parson Russell. The Australian and Irish Terriers have to have front legs which are perfectly straight. The Sealyham has to have its point of shoulder in line with its point of elbow. The Airedale has to show little space between its ribs and its hips. The Bedlington has to feature front legs that are wider apart at the chest than at the feet (the strangely-desired ‘horse-shoe front’). The Wire-haired Fox Terrier has to have its tail set high; the Smooth is expected to have its tail set rather high, and, in its forequarters, little or no appearance of ankle in front. These stipulations are not wise. They are so easily misapplied by those who have never seen a canine miner at work.

In his authoritative The Complete Book of the Dog of 1922, Robert Leighton summed up the varied origins of our terrier breeds: “Some of the breeds of terriers seen nowadays in every dog show were equally obscure and unknown a few years back. Fifty years ago the now popular Irish Terrier was practically unknown in England, and the Scottish Terrier was only beginning to be recognized as a distinct breed. The Welsh Terrier is quite a new introduction that a generation ago was seldom seen outside the Principality; and so recently as 1881 the Airedale was merely a local dog known in Yorkshire as the Waterside or the Bingley Terrier. Yet the breeds just mentioned are all of unimpeachable ancestry, and the circumstance that they were formerly bred within limited neighbourhoods is in itself an argument in favour of their purity. We have seen the process of a sudden leap into recognition enacted during the past few years in connexion with the white terrier of the Western Highlands, with the Cairn Terrier and with the Sealyham; and at the moment the hitherto ignored terrier of the Borders is receiving tardy recognition. Yet the West Highland Terrier was known in Argyllshire three hundred years ago, while the Sealyham Terrier was hunting the otter in Pembrokeshire when Wales was inaccessible to all but the most adventurous of travellers.” He has summed up, very neatly, the terrier heritage.

Foundation stock in the sporting terrier breeds often came from hunt kennels or working sources and so the breeding basis was sound. Gradually and remorselessly however, both the anatomies and the coefficients of inbreeding have in some of these breeds reached unacceptable levels and a rethink is now urgently required. Away from the show ring, unrecognised breeds, like the Fell, Sporting Lucas and Patterdale have thrived, not in large numbers, but in true terrier form. Newly-emerging breeds like the Parson Russell and Plummer Terriers are more popular than some age-old breeds, with the ubiquitous Jack Russells replacing the once heavily fancied Fox Terrier. If the twentieth century was the one in which the terrier breeds ‘arrived’, then the twenty-first century could be the one in which the terrier varieties ‘came and went’. What really must continue is the unquenchable spirit in this type of dog; breeds may in time just lose favour, but any breed bearing the description of terrier has to have that very special ‘get-up-and-go’, the never-say-die attitude of the true earth-dog. Are the sportsmen of the future truly going to guard the precious heritage of our terrier breeds? I have serious worries about this!